Early History of University Heights

Kumeyaay Land Acknowledgement

We respectfully acknowledge that the people of the Kumeyaay Nation are the original inhabitants of the unceded land now known as University Heights. We recognize the tremendous contributions of the Kumeyaay people to our region and thank them for their stewardship.

University Heights Begins in 1885

The development of University Heights began in 1885, after the completion of the Santa Fe transcontinental railroad, which spurred San Diego’s first period of large–scale urbanization. In 1887, a large tract of land overlooking Mission Valley was subdivided by the College Hill Land Association, a syndicate of businessmen owning land in the proposed subdivision.

The syndicate promised prospective buyers that a branch college of what would eventually become the University of Southern California would be located in University Heights.

On August 6,1888, Subdivision map #558 was filed with the San Diego County Recorder, delineating the University Heights subdivision. According to literature published by the syndicate, an endowment fund of $2 million would be created to help establish the college.

However, construction of the college never advanced beyond the planning stage, as the real estate boom suddenly burst in 1889.

The Grand State Normal School

A second attempt to bring an institution of higher learning to the area was initiated in 1898. The site of the aborted San Diego College of the Arts was donated to the State of California to build a “Normal School,” a state-sponsored teacher-training college.

A Neoclassic Revival college building, designed by local architects William S. Hebbard and Irving Gill, was completed and opened in 1899. The State Normal School was the forerunner of the present San Diego State University.

The Normal School operated in this location for over thirty years. In 1925, the Normal School was granted college status and, in 1931, was relocated to its present site on Montezuma Mesa. The old Normal School was converted into Horace Mann Junior High School but was demolished in the 1950s to make way for a parking lot at the Education Center between Campus Avenue and Normal Street.

Cable Cars Come to University Heights

University Heights was an early “streetcar suburb,” a residential area whose development was closely tied to direct access to downtown San Diego’s commercial and business center by cable, then electric-powered, trolleys.

Just like the more famous San Francisco cable cars, the San Diego Cable Railway traveled south along Fourth Street through University Heights all the way to L Street in downtown San Diego. The cable railway’s tracks entered University Heights at Fourth Street and Fillmore Avenue (today’s corner of Fourth and University in Hillcrest), where it traveled eastward until jogging northeast along University Boulevard (today’s Normal Street) to Carolina Street (today’s Park Boulevard).

Mission Cliff Gardens

After its purchase by the San Diego Electric Railway Company in 1898, the park was again renovated and renamed Mission Cliff Gardens. John D. Spreckels wished to showcase the area as a botanical garden rather than an amusement park.

In 1904, Spreckels chose Scottish-born landscape gardener John Davidson as the park’s superintendent and asked him to redesign the park into a botanical wonder. Davidson found that the soil beneath the park left much to be desired, consisting of hard adobe clay and scores of cobblestones. Undaunted, he proceeded to incorporate the cobblestones into the park’s landscape. He and his workers used them to line pathways, tier terraced gardens, and as a construction material for a series of walls throughout the park.

Two of these walls still survive–one surrounds the former lily pond at North Court and Mission Cliff Drive and the other is the impressive cobblestone wall along the north side of Adams Avenue from Park Boulevard to Mission Cliff Drive.

The Bentley Ostrich Farm

Also in 1904, John D. Spreckels invited Harvey Bentley to relocate his ostrich farm from Coronado. For an additional fee, visitors to the gardens could gaze upon a dozen or more ostriches around the farm. Fearless visitors could even ride the huge birds.

Across the street from the Ostrich Farm was William Hilton’s San Diego Silk Mill (l735 Adams Avenue). Silk production was a thriving industry by the turn of the century.

New Water Supply Spurs Growth

University Heights did not really start to develop until 1907, when the San Diego Electric Railway was extended east on Adams Avenue past the Trolley Barn at Park and Florida.

Also during this time, a lawsuit finally ended between Spreckels and one of his ex-partners, Elisha Babcock. The dispute was over the ownership and operation of the Southern California Mountain and Water Supply Company, which they had developed in the 1890s. The suit was settled in favor of Spreckels, who then supplied the city of San Diego with water.

Assured of an abundant supply of water, the city experienced a $6 million increase in new construction and improvements, including a major building program along Broadway in downtown San Diego. All of this building and commercial activity brought investors and new residents into the area.

New Trolley Line Brings Development to University Heights

Anticipating the potential for growth fueled by the extension of the trolley line, the University Heights Syndicate formed in 1902 to reorganize the development of University Heights.

The Syndicate planned to develop housing along the new trolley line on Adams Avenue east of Mission Cliff Gardens. The company’s first subdivision along the new trolley line extension was Valle Vista Terrace, a tract of luxury homes on Panorama Drive which provided magnificent views of Mission Valley and glimpses of the ocean.

The Adams Avenue Trolley Barn

In 1913, a massive trolley car barn was built on property adjoining the ostrich farm. The cavernous reinforced brick building was used to store and perform minor service to several hundred trolleys. Trolleys would exit and enter it through a series of switches off of Florida Street.

After the trolleys ceased running in 1949, the car barn was sold to the San Diego Paper Box Company, which manufactured corrugated cardboard boxes. In 1979, the building was sold and demolished to make way for a condominium project.

However, the land remained undeveloped until l991 when, through community efforts, the area was transformed into the present 8 1/2-acre Trolley Barn Park.

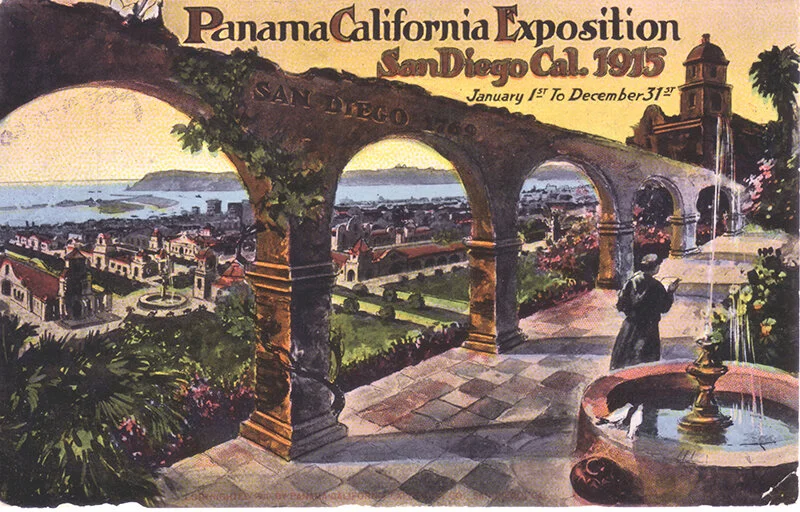

Panama-California International Exposition

To advertise San Diego’s remarkable growth and its potential for investment the San Diego Chamber of Commerce, proposed an exposition in Balboa Park.

After the announcement of the proposed Exposition, San Diego experienced a large-scale increase in home, hotel, and apartment construction. A number of structures in University Heights were built during that time. These developments are especially pronounced at the intersection of Adams Avenue and Park Boulevard. Here, passengers would transfer from the #1 trolley line on Park Boulevard to the Adams Avenue shuttle trolley line.

Popularity of Mission Cliff Gardens Declines

Due to the popularity of Balboa Park after the 1915 Panama-California International Exposition, and the development of Mission Beach by Spreckels in the 1920s, the popularity of Mission Cliff Gardens declined. The final blow was the death of Spreckels in 1926. Mission Cliff Gardens was closed in 1930 and relegated as a “Physical Non-Operating Property.”

After Davidson’s death in 1935, the gardens deteriorated. In 1942, the property was developed by the Spreckels interests to provide critically needed wartime housing. Parts of the cobblestone wall were breached at either end to facilitate automobile traffic.

Preservation Efforts in University Heights

Several vestiges of Mission Cliff Gardens survive and have been historically designated through the efforts of the University Heights Historical Society, including:

The former entrance to Mission Cliff Gardens on Adams Avenue at the end of North Avenue, including the redwood gate, and some of the palm trees.

The cobblestone wall that lined Adams Avenue from Park Boulevard to its dead end.

The cobblestone wall surrounding the former lily pond on Mission Cliff Drive at North Court, built by John Davidson and his workers. The former pavilion designed by William Hebbard stood just north of the pond.

The former entrance to the Ostrich Farm at Park and Adams, including the redwood gate and the cobblestone piers.

The cobblestone remains of a drinking fountain, which was once part of an ornate waiting station for the Number 11 trolley.

In addition to the properties landmarked by the University Heights Historical Society, many private property owners in University Heights have succeeded in having their homes historically-designated. This not only provides them with the opportunity for significant property tax benefits but preserves just a little bit of our history for generations to come.